Foundations | Course: Shape and Space

Table of Contents

- Lesson Overview

- Learn

- Practice

- Reflect

- Assignment

- Knowledge Check

Lesson Overview

This section is an overview of what you will learn by the end of this lesson.

- Identify and differentiate between positive space (the focus of a composition) and negative space (the surrounding area).

- Use spatial awareness to create balanced, intentional compositions.

- Understand figure-ground reversal and recognize its use in artworks that play with visual perception.

- Begin making creative decisions that use space to communicate meaning, balance, and tension.

Learn

Let’s begin with a simple but powerful truth: space is not empty.

In art and design, space isn’t just the background—it’s an active, powerful tool. Space helps define what’s important. It helps us breathe, move, and feel direction inside a composition.

Positive space: The primary focus of the composition.

Positive space is often the area that contains the main subject or elements you want your viewers to focus on.

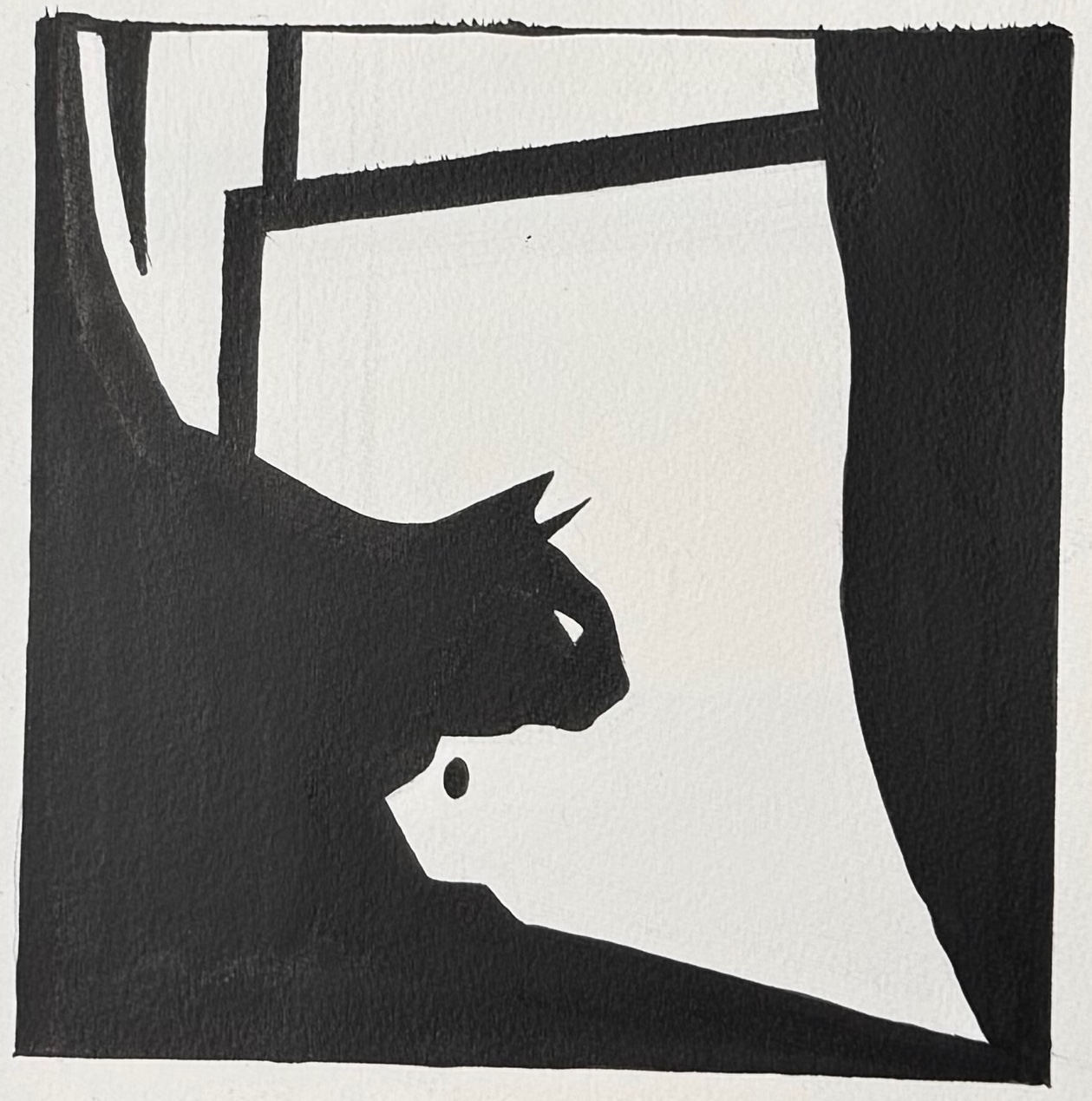

Negative space: The area that surrounds the primary focus of a composition, typically associated with the background of a piece.

Negative space is around and between the subject(s). It’s often considered the background—but it’s more than just filler. It gives your work structure, clarity, and even guidance.

Figure-ground reversal: A visual phenomenon that occurs when a shape can be perceived as either the figure or the ground

When the distinction between positive and negative space becomes ambiguous, viewers can flip between seeing one space as the subject or the background.

Sometimes what you don’t draw is just as important as what you do.

Real World Examples

Let’s look at how artists and designers use space across different disciplines. These examples were selected by our community to spark your curiosity and inspire your next sketch.

Architecture

Contemporary: Zaha Hadid’s fluid, futuristic buildings often emphasize positive space in unexpected ways, shaping the void as much as the structure.

Historical: Traditional Japanese architecture, like Shoji screens, uses negative space intentionally to invite calm and clarity into a structure. Open spaces between beams and windows aren’t “empty”—they’re purposeful.

Fine Art

Historical: Matisse’s paper cut-outs rely on bold, abstract shapes and the relationship between figure and ground. His use of white space is as loud as the color itself.

Contemporary: Kara Walker’s black paper silhouettes explore power and identity through high contrast and dramatic figure-ground relationships, often making viewers question what’s in the foreground and what’s not.

Photography

Historical: Dorothea Lange’s “Migrant Mother” holds space carefully—notice how the children’s faces are hidden and the negative space presses inward. The absence of detail in the background intensifies focus.

Contemporary: Photographer Fan Ho captured Hong Kong street life with strong light-and-shadow contrast. His use of empty alleyways or silhouetted stairwells emphasized drama through negative space.

Film

Historical: Film noir often relied on negative space and shadow to create mood and suspense. Think of the lonely lamp-lit desk surrounded by dark silence.

Contemporary: Directors like Wes Anderson use symmetrical compositions and lots of “breathing room” in their frames—often placing characters off-center, letting the background speak as loudly as the subject.

Unexpected Art Form: Papercutting

Artists like Béatrice Coron and Joe Bagley use only positive and negative space—nothing in between. Each cut removes or keeps paper to build entire worlds with balance and precision. It’s figure-ground reversal in action.

Practice

This section helps you observe, analyze, and create using positive and negative space.

Activity 1: Interpret what you see

Learning to observe first is the foundation of strong art-making. Before your pencil ever touches the page, your eyes must do the heavy lifting—training to notice subtle shapes, proportions, relationships, and rhythms. Observation builds visual literacy, helping you move beyond assumptions and really see what’s in front of you. The better you observe, the more accurate, intentional, and meaningful your work will become.

- Find 6 artworks (or use the unit resource gallery). Select 2 that show strong positive space, 2 that showcase clever negative space, and 2 that play with figure-ground reversal.

- Do a 3-5 minute sketch of each one. Focus on the relationship between figure and background rather than realistic detail.

- Label areas of positive and negative space. Make note of anything that surprised you—what did you “miss” at first glance?

Helpful hints to get you started.

Search by Keyword: If you’re looking online, try searching terms like “positive and negative space art,” “figure-ground reversal examples,” or “papercut silhouette art.”

Poster & Logo Design: Graphic design is full of clever use of space—check out logos (like FedEx or WWF) or minimalist posters.

Famous Artists to Explore:

- M.C. Escher – master of figure-ground reversals

- Henri Matisse – brilliant use of positive/negative space in his cut-outs

- Kara Walker – silhouette work with high-contrast storytelling

- Ellsworth Kelly – clean, bold compositions that use space as subject

Activity 2: Analyze master works

In this activity, you are going to do what art professors call a “master study”. A master study is the process of analyzing another artist’s work to understand their creative process. A master work was, originally, a piece of work from an artisan that would be presented to a guild as evidence of qualification for the rank of master. Nowadays, we define it as a work that is completed by an artisan who society has deemed a master in their area of expertise.

- Find 5 master works that inspire you. You can find these yourself or use the unit resource gallery.

- If you’re choosing to find your own, these can be from any famous artist: from renaissance artists to anime artists, or influencers on social media. The idea is that they need to be well-known.

- For each, take 5 minutes to study, observe and mentally note where lines are formed without a physically drawn line.

- Now sketch the outline of the major shapes of the each work. Focus on the demonstrating where the original artist used explicit and implicit lines to create the work.

- After your done, briefly note what you learned about how that artist used explicit and implicit lines in their artwork.

Helpful hints to get you started

- For finding master works:

- Start with What You Love: Whether it’s a Renaissance painting, an anime panel, or a scene from your favorite film—if it’s well-crafted and well-known, it counts!

- Use Museum Websites: Sites like the Met, MoMA, or the National Gallery let you zoom in and explore high-res images for free.

- Think Cross-Disciplinary: Fashion design, comic books, and architecture all use space in compelling ways—don’t limit yourself to paintings!

- For analyzing the works:

- Look for Edges: Ask yourself, “What defines the shape here?” Is it a solid outline (positive space), or the shape made by what’s missing (negative space)?

- Trace Major Shapes: Before you sketch, mentally or lightly trace the big shapes first—ignore fine detail.

- Notice the Visual Balance: Where is the weight in the image? Does one side feel “heavier”? That often means more positive space.

- Ask Why: Why might the artist have made that area empty? What emotion or movement does that create?

Activity 3: Evaluate your surroundings

- Let’s create something new and experiment with the use of explicit and implicit lines in your sketchbook.

- Choose a location like near a window, in a hallway, in a room where you can see interesting alignments. You’re looking for furniture, windows, doorframes, shadows, beams of sunshine, etc).

- Before you start drawing, take up to 2 minutes to observe the scene. Look for lines that aren’t physically drawn but appear through the alignment of objects or edges (for instance, the corner where two walls meet, or the line where a window frame lines up with a piece of furniture.)

- Roughly outline the major shapes you see. Aim to guide the viewer’s eye through your composition – imagine them as “paths” for the eye to follow and that organize the space.

- After you’re done, briefly note which lines are explicit and which are implicit.

Helpful hints to get you started.

- Hints for Observation

- Take a Photo First (Optional): If something is hard to draw live, take a picture and study the composition from your phone or computer.

- Sit Still and Breathe: Take a full minute before drawing to just look. Let your eyes explore. Notice shadows, gaps, shapes between objects—those are often your negative spaces.

- Use a Viewfinder: Cut a rectangle into a piece of paper and use it to “crop” your scene like a camera. It helps isolate space and composition.

- Hints for Drawing

- Try Blocking In Shapes: Start by lightly shading in the background (negative space) rather than outlining the objects themselves.

- Draw What’s Not There: Focus on the “gaps” between things like chair legs, wall corners, or the space under a table. Those are just as important as the objects themselves!

- Flip It: After you draw once starting with negative space, try again starting with positive space. Which one feels clearer or more balanced?

Assignment

5 days of Lines

Creating art is a physical activity and with all physical activities we recommend building a habit of observing and drawing lines daily (or as often as you can). This will reinforce the concepts you have learned and slowly create a sixth sense that you will execute but rarely think about.

Day 1: Choose one simple object in your home (like a mug or a small plant). Draw it focusing only on its explicit lines (the clear outer edges).

Day 2: Look out a window or into a room and sketch the main implicit lines—edges or shapes that lead your eye around the space without being explicitly drawn.

Day 3: Combine both types of lines in a single composition. For example, sketch a corner of a room, capturing some explicit lines (window frames, furniture edges) and implicit lines (where surfaces line up or shadows meet).

Day 4: Revisit the internet for quick inspiration. Find a single reference image—architecture, artwork, fashion—and do a 5-minute pencil sketch emphasizing the lines you observe.

Day 5: Reflect on your progress. On a fresh page, quickly sketch any subject you like and try to incorporate both explicit and implicit lines. Then, write a few sentences about how your understanding of line has changed during these five days.

Reflect

After completing the activities above, take a moment to reflect on at least three of the following questions. Write your responses in your sketchbook or separate sheet of paper.

- What did you notice when studying and observing other works of art or even the environment around you? Which type of lines stood out the most and why?

- In your sketches, which lines do you feel control the viewer’s eye the the most and why?

- How does this change your perception of art and design? Do you notice compositional “pathways” that you didn’t see before?

- How does this change your process for creating art? Or does it? Why or why not?